"Which is worst - the white black man, or the black white man, to be black on the outside, or to be black on the inside?" [22]

Agrippa Hull

The Sentimental Patriot Continued

The man behind the portrait was very three-dimensional. The soon-to-be American Patriot was born on March 7th, 1759 in Northampton Massachusetts during the Seven Years War. His supposed princely father was named Amos Hull, and his mother Bathsheba. Both had been slaves that had gained their freedom. Just like his four other siblings, two girls and two boys, Hull was baptized in the local Congregational Church. Agrippa’s unusual name pays homage to Agrippa II, the son of Herod Agrippa I in the New Testament, who finds truth in the gospel later in life, just like this Agrippa did.

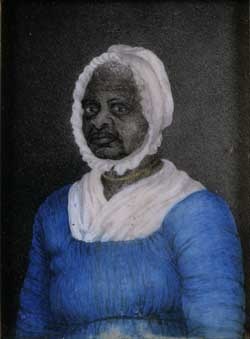

By 1761, three members of Hull’s family had died, which might explain the sadness evident in his portrait. The dead included one of his sisters who passed away in infancy, one three-year-old brother, and Amos Hull, Agrippa’s father had died that year. Struggling financially, Bathsheba Hull took to the road, sending the seven-year-old Agrippa to live with her friends the Binneys, a well off African American family living in Stockbridge, just forty miles west of Agrippa’s first home in Northampton. It seems logical that in order to be a good father, one must have a good (and present) father, but that was not the case for Agrippa Hull.

At this time Stockbridge was a young town, founded thirty-two years before Agrippa was introduced to his new family. The small, beautifully peaceful Stockbridge was home to many. Most of the population at this time were Native American, but there were some white families, and even fewer free black families living among the leafy mountains. This diversity within the town let Agrippa grow up in a different America than almost every other child at this time. He was given the opportunity to play with children who spoke better Mohawk and Mahican than English. Stockbridge had three Indian men and two white men comprising the board of Selectmen, and mixed race marriages were not uncommon.[7] But this did not last long. Even so, this arrangement must have influenced Hull greatly.

By the 1770s, the French and Indian War was over, meaning the Native Americans in Stockbridge no longer needed to be there according to the state, isolated from their other tribesmen. The seventy-five percent of the land they used to own was quickly taken from under their feet by white men through trickery and conspiracy, leaving the Native Americans with only six percent of the land in Stockbridge. To add insult to injury, the Natives also lost their places in government. This is all sadly articulated in the Stockbridge Museum and Archives, near Agrippa's hanging portrait.

In the year 1771, Agrippa’s family was once again united, his mother returning to collect him from the Binneys with her new husband, Philemon Lee and Agrippa’s older sister. Four years later on April 19th, 1774, the American Revolution began. In the year of Hull’s eighteenth birthday, three years after the war had started, Agrippa joined the tavern keeper Isaac Marsh’s First Stockbridge Company. It is during this time the first physical description of Hull was recorded, the Berkshire County muster master jotting down: “Stature, 5ft, 7in; complexion, black, hair, wool."[8] This brief description paints a blurry youthful image of the man only known from a portrait and a daguerreotype from his later years in life.

Very shortly after joining the army, Hull was assigned to General Paterson as his orderly. By 1777, Paterson had already accomplished great feats, and Hull joined him in the midst of that greatness at Fort Ticonderoga. Hull was soon given the playful nickname, “Grippy," from his fellow soldiers, while making their way south to combine with Washington’s army of around 12,000 men at Valley Forge. It was within this camp Kościuszko, Paterson, and Hull first crossed paths, at a supper on May 16, 1777.[9]

By 1761, three members of Hull’s family had died, which might explain the sadness evident in his portrait. The dead included one of his sisters who passed away in infancy, one three-year-old brother, and Amos Hull, Agrippa’s father had died that year. Struggling financially, Bathsheba Hull took to the road, sending the seven-year-old Agrippa to live with her friends the Binneys, a well off African American family living in Stockbridge, just forty miles west of Agrippa’s first home in Northampton. It seems logical that in order to be a good father, one must have a good (and present) father, but that was not the case for Agrippa Hull.

At this time Stockbridge was a young town, founded thirty-two years before Agrippa was introduced to his new family. The small, beautifully peaceful Stockbridge was home to many. Most of the population at this time were Native American, but there were some white families, and even fewer free black families living among the leafy mountains. This diversity within the town let Agrippa grow up in a different America than almost every other child at this time. He was given the opportunity to play with children who spoke better Mohawk and Mahican than English. Stockbridge had three Indian men and two white men comprising the board of Selectmen, and mixed race marriages were not uncommon.[7] But this did not last long. Even so, this arrangement must have influenced Hull greatly.

By the 1770s, the French and Indian War was over, meaning the Native Americans in Stockbridge no longer needed to be there according to the state, isolated from their other tribesmen. The seventy-five percent of the land they used to own was quickly taken from under their feet by white men through trickery and conspiracy, leaving the Native Americans with only six percent of the land in Stockbridge. To add insult to injury, the Natives also lost their places in government. This is all sadly articulated in the Stockbridge Museum and Archives, near Agrippa's hanging portrait.

In the year 1771, Agrippa’s family was once again united, his mother returning to collect him from the Binneys with her new husband, Philemon Lee and Agrippa’s older sister. Four years later on April 19th, 1774, the American Revolution began. In the year of Hull’s eighteenth birthday, three years after the war had started, Agrippa joined the tavern keeper Isaac Marsh’s First Stockbridge Company. It is during this time the first physical description of Hull was recorded, the Berkshire County muster master jotting down: “Stature, 5ft, 7in; complexion, black, hair, wool."[8] This brief description paints a blurry youthful image of the man only known from a portrait and a daguerreotype from his later years in life.

Very shortly after joining the army, Hull was assigned to General Paterson as his orderly. By 1777, Paterson had already accomplished great feats, and Hull joined him in the midst of that greatness at Fort Ticonderoga. Hull was soon given the playful nickname, “Grippy," from his fellow soldiers, while making their way south to combine with Washington’s army of around 12,000 men at Valley Forge. It was within this camp Kościuszko, Paterson, and Hull first crossed paths, at a supper on May 16, 1777.[9]

Exactly two years after that meeting and many of Grippy’s stories about his father (the African Prince) later, in May of 1779, Hull was reassigned as Tadeusz Kościuszko’s orderly.[10] This arrangement was made by General Paterson, who could clearly see the bond forming between the two men. At one point during this pairing, Kościuszko set out to examine the American's position at the Hudson Highlands, leaving Hull in charge of his quarters for two to three days. What Grippy did next came to be his most retold story.

First, Hull called upon all the slaves and free black men of the camp and without further ado, Agrippa Hull began hosting a party in General Kościuszko’s quarters. Agrippa adorned his friend’s formal uniform, a navy blue coat with an elegant cherry collar, a four-cornered hat topped with ostrich feathers, a sash, sword, and shining epaulets, possibly the same ones the General wears in his portrait above. Lacking boots, since Kościuszko had worn them on his trip, Hull painted his shins with dark shoe polish to "top off" the costume.[11] Playing the officer, Grippy strutted about and ordered the servants to do this and that, asking one for a glass of water. Acting unsatisfied with the amount of time it was taking the water retriever, he called again and again.

That night, the General returned unexpectedly. It was Kościuszko who brought Agrippa’s water. Once the white Engineer was spotted, there was quite a ruckus. Expecting to be whipped by the Pole, all Grippy’s guests fled instantly, some out windows, and the rest flooding through the door.[12] Shaking in his nonexistent boots, Grippy prepared for the worst. Flinging himself at Kościuszko’s feet, he begged for mercy. Agrippa Hull tells the story with the exchange going like this, as recorded in Catherine Sedgwick’s story entitled “West Point”,

“‘I deserve to be punished, sir!’ said I.

‘No, no, Grippy,’ said he, ‘come with me. I’ll take you round to the officers’ tents, and introduce you as an African Prince. Don’t speak, but mind my signs, and obey them.’

‘I shall die, sir,’ said I."[13]

After reassuring Grippy that he would not die, the grinning General introduced Agrippa by a long name to the highest commander at the camp. Thoroughly convincing in his introduction, some of the officers went about believing Agrippa an African Prince. A throne was informally thrown together for Grippy and soon he was being offered wine, brandy, and even a pipe.[14] Obeying Kościuszko’s signs, Grippy accepted all that he was offered, and that was punishment enough for Agrippa Hull, for the man hated both smoking and drinking. After seeing this on Hull’s face, the Polish Engineer took pity on him, clapping him on the back and telling him to go about his business.[15] The moral Grippy would finish this tale off with is, “from that day to this, I have never tried to play any part but my own."[16] As for punishment, Grippy received it the next morning when he awoke with a terrible hangover.[17] Reliving this hilarious humiliation must have made Hull a very humble man.

As facial expressions go, the one Agrippa Hull is wearing in his painting is quite strange. At first glance, he seems boringly serious and sunken. However, once some time is spent examining his features, the turned up lip, one eyebrow slightly higher than the other, it looks like he might have just told a story, and what better story to tell his photographer, Anson Clark, than his most famous one, involving boot polish, patriotism, and the General?

The American Revolution ended much too quickly for Hull in 1783, which was certainly a unique opinion on both sides of the war. His reason behind this desire was that he did not want to separate from his beloved friend General Tadeusz Kościuszko. As a parting gift, the Polish Engineer bestowed an expensive Polish flintlock pistol on Hull. Departing from Philadelphia with his present, Hull walked north to West Point. There Hull was discharged from the army and given a “settlement certificate” of £80. Like all the other soldiers, Hull would not be receiving anything in the way of pension until 1818, thirty-five years later, when Congress passed an act to aid impoverished Revolutionary veterans, which a year later they would cut Agrippa off from because he was well enough off by ther calculations. Disappointed but undeterred, Hull was not done with the War Department and his pension.

Returning to Stockbridge, home to roughly a thousand whites and forty free African Americans at this time, Hull took up work in Theodore Sedgwick’s house. In 1781, Sedgwick had taken on the Bett and Brom case, and slavery was nearly done away with in Massachusetts. Because of his employment with Sedgwick, Hull was far better off than the other free African Americans in the surrounding area. After winning her freedom, Elizabeth Freeman, formerly known as Mumbett, came to work for Sedgwick too. (Her painting can be seen below on the left.) Some of Hull's opinions on slavery might have been influenced by Freeman.

Hull had plenty of his own opinions on slavery. As to be expected, he was extremely against it, approving of the harboring of escaped slaves. Even so, he was a Patriot at heart and had fought for his country. He supported everyone who tried to help slaves, but he would not have taken up arms in the Civil War to fight against the laws he had had a part in fighting to create. Through and through, Grippy was a patriot.

In 1785, Hull married Jane Darby, a fugitive slave who had fled from an abusive master. After careful economy for many years, by 1792 Hull owned eleven acres of land, allowing him to vote. Five years later, in 1797, after being apart for thirteen years, Hull and Kościuszko were reunited briefly in New York. That year continued happily for Grippy, giving him his second child, James. His daughter Charlotte had been born the previous year, and his third child, Aseph would be born later in 1802. The year after, much to Agrippa’s delight, Elizabeth Freeman became his immediate neighbor. Now, Agrippa had a family, a lovely neighbor and he could vote, he must have been ecstatic.

First, Hull called upon all the slaves and free black men of the camp and without further ado, Agrippa Hull began hosting a party in General Kościuszko’s quarters. Agrippa adorned his friend’s formal uniform, a navy blue coat with an elegant cherry collar, a four-cornered hat topped with ostrich feathers, a sash, sword, and shining epaulets, possibly the same ones the General wears in his portrait above. Lacking boots, since Kościuszko had worn them on his trip, Hull painted his shins with dark shoe polish to "top off" the costume.[11] Playing the officer, Grippy strutted about and ordered the servants to do this and that, asking one for a glass of water. Acting unsatisfied with the amount of time it was taking the water retriever, he called again and again.

That night, the General returned unexpectedly. It was Kościuszko who brought Agrippa’s water. Once the white Engineer was spotted, there was quite a ruckus. Expecting to be whipped by the Pole, all Grippy’s guests fled instantly, some out windows, and the rest flooding through the door.[12] Shaking in his nonexistent boots, Grippy prepared for the worst. Flinging himself at Kościuszko’s feet, he begged for mercy. Agrippa Hull tells the story with the exchange going like this, as recorded in Catherine Sedgwick’s story entitled “West Point”,

“‘I deserve to be punished, sir!’ said I.

‘No, no, Grippy,’ said he, ‘come with me. I’ll take you round to the officers’ tents, and introduce you as an African Prince. Don’t speak, but mind my signs, and obey them.’

‘I shall die, sir,’ said I."[13]

After reassuring Grippy that he would not die, the grinning General introduced Agrippa by a long name to the highest commander at the camp. Thoroughly convincing in his introduction, some of the officers went about believing Agrippa an African Prince. A throne was informally thrown together for Grippy and soon he was being offered wine, brandy, and even a pipe.[14] Obeying Kościuszko’s signs, Grippy accepted all that he was offered, and that was punishment enough for Agrippa Hull, for the man hated both smoking and drinking. After seeing this on Hull’s face, the Polish Engineer took pity on him, clapping him on the back and telling him to go about his business.[15] The moral Grippy would finish this tale off with is, “from that day to this, I have never tried to play any part but my own."[16] As for punishment, Grippy received it the next morning when he awoke with a terrible hangover.[17] Reliving this hilarious humiliation must have made Hull a very humble man.

As facial expressions go, the one Agrippa Hull is wearing in his painting is quite strange. At first glance, he seems boringly serious and sunken. However, once some time is spent examining his features, the turned up lip, one eyebrow slightly higher than the other, it looks like he might have just told a story, and what better story to tell his photographer, Anson Clark, than his most famous one, involving boot polish, patriotism, and the General?

The American Revolution ended much too quickly for Hull in 1783, which was certainly a unique opinion on both sides of the war. His reason behind this desire was that he did not want to separate from his beloved friend General Tadeusz Kościuszko. As a parting gift, the Polish Engineer bestowed an expensive Polish flintlock pistol on Hull. Departing from Philadelphia with his present, Hull walked north to West Point. There Hull was discharged from the army and given a “settlement certificate” of £80. Like all the other soldiers, Hull would not be receiving anything in the way of pension until 1818, thirty-five years later, when Congress passed an act to aid impoverished Revolutionary veterans, which a year later they would cut Agrippa off from because he was well enough off by ther calculations. Disappointed but undeterred, Hull was not done with the War Department and his pension.

Returning to Stockbridge, home to roughly a thousand whites and forty free African Americans at this time, Hull took up work in Theodore Sedgwick’s house. In 1781, Sedgwick had taken on the Bett and Brom case, and slavery was nearly done away with in Massachusetts. Because of his employment with Sedgwick, Hull was far better off than the other free African Americans in the surrounding area. After winning her freedom, Elizabeth Freeman, formerly known as Mumbett, came to work for Sedgwick too. (Her painting can be seen below on the left.) Some of Hull's opinions on slavery might have been influenced by Freeman.

Hull had plenty of his own opinions on slavery. As to be expected, he was extremely against it, approving of the harboring of escaped slaves. Even so, he was a Patriot at heart and had fought for his country. He supported everyone who tried to help slaves, but he would not have taken up arms in the Civil War to fight against the laws he had had a part in fighting to create. Through and through, Grippy was a patriot.

In 1785, Hull married Jane Darby, a fugitive slave who had fled from an abusive master. After careful economy for many years, by 1792 Hull owned eleven acres of land, allowing him to vote. Five years later, in 1797, after being apart for thirteen years, Hull and Kościuszko were reunited briefly in New York. That year continued happily for Grippy, giving him his second child, James. His daughter Charlotte had been born the previous year, and his third child, Aseph would be born later in 1802. The year after, much to Agrippa’s delight, Elizabeth Freeman became his immediate neighbor. Now, Agrippa had a family, a lovely neighbor and he could vote, he must have been ecstatic.

This great happiness turned to sadness when his first wife, Jane Hull, passed away sometime between their third son’s birth in 1802 and Hull’s subsequent remarriage in 1813. Hull was married to Margret “Peggy” Timbroke, who was thirty-years his junior, just seven years older than Agrippa Hull’s oldest daughter, Charlotte.[18] Her likeness, as well as Hull's was captured in a daguerreotype. The actual daguerreotype can be seen underneath Hull's Portrait at the Stockbrige Museum and Archives.

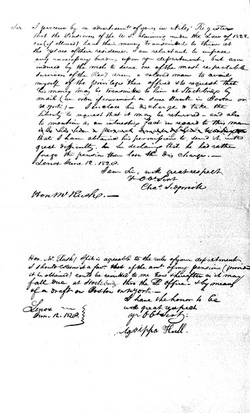

Hull continued to fight for what he believed in long after being released from the army. The War Department changed their pension rules in 1826, allowing retired soldiers to receive pension if their property did not exceed a three-hundred dollar value. Two years later, Hull reapplied for his pension. With help from Charles Sedgwick, Theodore Sedgwick’s son, Hull reluctantly sent a letter and his discharge papers, signed by George Washington, to Richard Rush, the Acting Secretary of State.[19] The brief passage Hull wrote at the bottom, proves that he was an educated man, which is a part of the strange aura found in Hull's Portrait.

Hull continued to fight for what he believed in long after being released from the army. The War Department changed their pension rules in 1826, allowing retired soldiers to receive pension if their property did not exceed a three-hundred dollar value. Two years later, Hull reapplied for his pension. With help from Charles Sedgwick, Theodore Sedgwick’s son, Hull reluctantly sent a letter and his discharge papers, signed by George Washington, to Richard Rush, the Acting Secretary of State.[19] The brief passage Hull wrote at the bottom, proves that he was an educated man, which is a part of the strange aura found in Hull's Portrait.

In the year of 1844, Agrippa Hull made a return trip to West Point. Here, he laid eyes on a statue of his great friend, Tadeusz Kościuszko, who had passed away in 1817.[20] Catherine Sedgwick wrote, “Agrippa was one of a large party that included the young, the gay, and the beautiful; but he was, as was most fitting, the most noticed and honored of them all."[21] Before the statue of his deceased companion, Agrippa Hull, to the delight of the spectators, retold his famous story of humiliation. It must have been a very emotional day for Hull.

[7] Nash and Hodges, 1, 11, 13, 14, 15.

[8] Ibid, 17, 19.

[9] Ibid, 21, 49, 52.

[10] Ibid, 55.

[11] Alex Storozynski, The Peasant Prince (New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books, 2009), 72, 73.

[12] Catherine Sedgwick, "West Point by Miss Sedgwick," Juvenile Miscellany, January/February 1833, 243.

[13] Ibid, 244.

[14] Storozynski, 73.

[15] Sedgwick, 244.

[16] Ibid, 245.

[17] Storozynski, 74.

[18] Ibid, 80-82, 84, 90, 94, 149, 195-197, 261, 297

[19] Ibid, 249, 250.

[20] Ibid, 247.

[21] Sedgwick, 245.

[22] Nash and Hodges, 261.

[8] Ibid, 17, 19.

[9] Ibid, 21, 49, 52.

[10] Ibid, 55.

[11] Alex Storozynski, The Peasant Prince (New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books, 2009), 72, 73.

[12] Catherine Sedgwick, "West Point by Miss Sedgwick," Juvenile Miscellany, January/February 1833, 243.

[13] Ibid, 244.

[14] Storozynski, 73.

[15] Sedgwick, 244.

[16] Ibid, 245.

[17] Storozynski, 74.

[18] Ibid, 80-82, 84, 90, 94, 149, 195-197, 261, 297

[19] Ibid, 249, 250.

[20] Ibid, 247.

[21] Sedgwick, 245.

[22] Nash and Hodges, 261.