"It is not the cover of the book, but what the book contains that is the question. Many a good book has dark covers."[6]

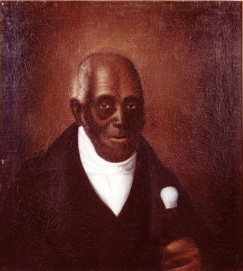

Agrippa Hull

The Sentimental Patriot

Being fatherless at a young age, Agrippa Hull continuously claimed to be the son of an African prince, but that was just a small part of his outstanding legacy. This charismatic storyteller served in the Rebels' American Revolution as Tadeusz Kościuszko’s orderly, and they formed a life-long friendship. Now, Hull’s portrait, created from a daguerreotype, hangs in the library of his home town, the Stockbridge Library, located in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Outside of Massachusetts, the memory of Hull’s existence seems to have faded away almost completely, but in his long life of eighty-nine years, “Grippy," as he came to be known, was a modestly well-connected man, his story intertwining with George Washington’s, the signer of his discharge papers, General Paterson’s, General Kościuszko’s, Mumbet’s, and Stockbridge native Theodore Sedgwick’s, his employer for several years. These connections and his confident personality helped Hull avoid the scoffing of his white neighbors. Through careful economic saving, Hull managed to become the wealthiest African American in his town, pretty good for the son of an African Prince.[1] Being the sparse spender he was, it’s a miracle Grippy’s likeness was ever captured, with daguerreotype “prices, from $2 to $3, including cases or frames,"[2] in 1844. The Portrait of Agrippa Hull, done anonymously in 1848, captures the incredible individuality of Agrippa Hull, sentimental soldier, loving husband and father, and clever minded man.

Agrippa Hull’s portrait is unique, just like he is. It is rare to see portraits of African Americans from the time of the American Revolution; two others include Elizabeth Freeman's (otherwise known as Mumbet) and Phillis Wheatley's. Both of them were women, who at one point or another were enslaved, Agrippa, on the other hand, was a free man all his life.[3] Grippy’s portrait stands out from the crowd with its sharp, contrasting colors. Sitting in the center of the canvas, Hull is wearing a regal white shirt with a white cravat tied around his neck. Over the white shirt is a black vest and black jacket, fancy clothes for the simple man he was. Clutched in his left hand is his walking stick, appropriate because Hull was eighty-five when the daguerreotype was taken.[4] The visual aspect of the cane is quite pleasing, the tip white to match the shirt while contrasting with the suit and the rest black, blending in with his suit. Hull’s face does not lack wrinkles, but still manages to seem youthful and optimistic, a smile visible in his eyes.[5]

[1] Gary B. Nash and Graham Russell Goa Hodges, Friends of Liberty: A Tale of Three Patriots, Two Revolutionaries, and the Betrayal that Divided a Nation: Thomas Jefferson, Tadeusz Kosciuszko and Agrippa Hull (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2008), 11.

[2] Richard Bolt, "Anson Clark Ad", Courtesy of the Berkshire County Library Anson Clark Collection.

[3] Nash and Hodges, 84, 203, 260.

[4] Richard Bolt, "Anson and Edwin H. Clark: Pioneering Daguerreotypists of Western Massachusetts", The

Daguerreian Annual 1991 (The Daguerreian Society, 1991) 84.

[5] Nash and Hodges, 262.

[6] Ibid, 261.

[2] Richard Bolt, "Anson Clark Ad", Courtesy of the Berkshire County Library Anson Clark Collection.

[3] Nash and Hodges, 84, 203, 260.

[4] Richard Bolt, "Anson and Edwin H. Clark: Pioneering Daguerreotypists of Western Massachusetts", The

Daguerreian Annual 1991 (The Daguerreian Society, 1991) 84.

[5] Nash and Hodges, 262.

[6] Ibid, 261.